How to reconnect humans to nature?

- Nick Keppel-Palmer

- Jan 26, 2021

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 27, 2021

The critical challenge for the Good Growth Company in delivering on our vision of environmental regeneration has finally come into view: we've got to deal with the humans.

That means finding a way to integrate planetary health with human prosperity - because the way we humans have evolved to prosper is fundamentally at odds with a healthy planet.

We prospering from the planet, not with it.

Our way of living is killing millions of animals

This morning we were on a call talking about the latest Zud - the occasional severe Mongolian winter event that wipes out a lot of livestock. In one particular region the local NGO reckons that out of 4.9m animals 3m will die this winter - with a devastating impact on incomes and livelihoods. (And that's before any Covid effect).

But here's the thing - that region shouldn't have nearly so many animals. The herds have grown bigger as the relentless and inevitable consequence of a cashmere industry that can't get enough, itself a product of a market driven, growth obsessed economic model that can't get enough.

So when the cold comes, there's not nearly enough food, so millions of animals die and the primary income stream for the herders in that place is wiped out. And - of course - they then feel compelled to start again and to rebuild the herds.

There wouldn't be so many animals if nature had been left to do its thing. And if nature had been left to its thing the death and damage would be minimal. But we humans came and dumped our economic model onto that place to stretch it beyond its capacity to support so many animals - so this massacre is on us. (But of course the vast majority of us have no idea that it has even happened).

So if we want to fix the environment (and we do) why not ignore the humans?

"Alcohol - the cause of and the solution to all of life's problems" - H.Simpson

It is very tempting to think (and I know many people who do) that we should keep humans out of any environmental restoration program, to think that one of the first steps to take in cleaning the place up is (and I quote) "to get the people out of the f***ing place and let nature recover".

The lovely "Rewilding" (or better "Wilding") movement demonstrates what can be done when a distinct piece of land can be hived off and fenced off from human activity and - pretty much - given back to nature. And yet....it's kind of no coincidence that most rewilding projects are on land that really does belong to someone quite far sighted (and normally rich) so is land that can be 'reclaimed' from humans without too much disruption.

And for sure such projects are a heck of lot easier for not having to worry too much about the people who live in (and from) the place.

But.....these are exceptional places and not the commons. If we're going to restore the planet we have to restore the commons, and that means we cannot ignore (tragically) the way in which we the people make a living from the commons.

So even if human activity screwed it up in the first place, Homer's right, humans must be central to the solution. We're not going to reverse climate change and species loss without addressing how we reintegrate and reconnect the way we live to nature.

But how?

Integrating human wellbeing and environmental health is the critical challenge for the regenerative age.

This is not an exaggeration - I think this is the toughest and most crucial challenge in fixing the planet. We have to find a way - at both ends of the chain - of switching our mode of behaviour so that we are no longer consuming and producing at the expense of the planet.

So what we mean by 'integrating human wellbeing with environmental health' is way, way beyond what most environmental programs call "community engagement". If you've ever been on a management training course you'll know what 'community engagement' feels like - turning up to the course is what counts most. Scandalously, several "sustainable" certification schemes lean heavily on participation statistics as a proxy for *actually* doing something about restoring the environment. (One "sustainable" badging outfit even promotes its program as a "sustainability standard" despite a self reported 13% attendance score for its training programs. And that's just attendance - not compliance).

So if we're going to do it we should do it properly - and that means getting to the bottom of the 3 big issues that shape how humans end up screwing up the environment (even if they don't want to).

1 - "homo economicus"

We have a couple of recovering economists in the Good Growth Company. It's not their fault but they do have a tendency to take a dim view of humanity - people only do what they do because they are fundamentally economic beings.

This idea of humans as having no intrinsic motivations aside from moolah pervades our entire economics, business and government systems. We are "consumers" or "producers" - shopper-bots and producer-bots that sit at either end of economic chains. Defined not as humans but as economic inputs.

The "homo economicus" dogma extends through the whole chain - processors will only process what pays them the most, herders will only engage with a program if you pay them.

"Homo economicus" is nonsense of course as brave people like Kate Raworth are now pointing out - but the idea of us as only responding to economics has leached into every aspect of life, including sustainability programs and brands with their obsessions in linking behaviour to money or premiums. (For a take down of greenwash brands - and specifically in the case of Naadam the impossibility of their pricing - look at this article: https://shopvirtueandvice.com/blogs/conscious-shopping/ethical-sweaters)

It is the casting of humans as economic beings that disconnects us (all) from nature.

You don't know that millions of animals are dying - right now - in Mongolia because the brand selling you that sweater has no interest in you knowing that. They just want your money.

This is a big problem. So if our version of fixing the environment starts with paying people to farm in a different way or to join our certification scheme then all we are doing is perpetuating the economic-human problem. For humans to prosper with nature as opposed to from nature we must not start with the money - we have to start with reinvigorating the relationship between humans and place.

2. Time

Guess what - it turns out that nature doesn't run at the same pace as humanity. It takes an age to turn an environmental corner. Halting, then reversing degradation takes a timespan that is - in human terms - multi-generational.

Changing and integrating the way humans prosper so that it's aligned with the health of the environment in which they live is not a quick fix - we reckon 3 or more likely 4 generations.

There's a land future project in Australia that asked the current farmers on each piece of land what they hoped to leave for their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and - specifically - what they needed to do to their farm to achieve that aim.

What they all wanted to leave was a "healthy" environment, abundant with good things. But when pressed for specifics about what that meant not one could answer - "healthy" in 100 years might mean all sorts of things. The place would have to adapt. How could anyone say that crop X or livestock Y was what would lead to "healthy"? What they needed was to become stewards of the place, to work with the place, to maintain and reinforce its health for generations to come.

It's kind of obvious but of course the rhythm of business (5 year cycles if you are lucky) is nowhere near long term enough for this kind of endeavour.

If we do ignore the long term realignment of humans in the place to prosper with that place, then the moment any conservation program ships out of any place all will revert to how it was before. Even philanthropy doesn't have the patience to fund programs for multiple generations.

And of course this kind of long term view simply does not fit with the wham bam speed of equity investment cycles (of any investors - even impact investors). When "short term" in environmental terms means 3 or 4 decades then there is no prevailing equity model that has a long enough view to stay the course. Which is why we think the financing of the ecosystem work we are undertaking requires a financing model that is geared to the rhythm of nature. More on this soon.

3. Identity - the big one

But scratch away at the root cause of the problem and something else comes into view.

We humans, at a very deep level, consider ourselves to be "other" from nature.

And not just "other" - fundamentally we believe ourselves superior to the natural world. We believe that we have sentience at a level no other species has. We believe (therefore) that it is OK for us to see other living things as existing for our benefit.

This "otherness" is all pervasive. It is so deeply ingrained that we barely notice. In our language we use animal terms as pejorative ("pig"). We have religions that reinforce the idea that Man has "dominion over the fish of the sea, over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, over all the earth and over every creeping thing that creeps on the earth" (page 1 of the Bible).

This "otherness" is explored brilliantly in this WWF paper from 2009 (on eco-campaigning - but the analysis applies beyond communication).

These three issues - that our economics compel us to extract from nature, that short-termism only exacerbates this, and that deep down we really do believe that nature exists for us and that we are somehow not part of it but above it - cannot be ignored.

Love is all we need (plus a new economic model)

Here's the good news - we absolutely can do this. We can do this because we are not actually economic beings (as Rutger Bregman points out in Humankind) more big soppy and sentimental love machines. When we fall in love with something we do all we can for it.

The flipside of this is that when we don't love something - or feel "other" from it - we tend to treat it badly. And that's what's happened to nature. Our in built otherness and our miserable economic system has pushed us out of love for the planet.

That we can fix - with a new economic system that operates at the rhythm of and for nature, and with a new relationship that makes us part of, not distant from, nature.

So how? Here's the sketchy beginnings of an answer

Any approach to integrating the wellbeing of humans in the place to the health of the place must:

shift the economics away from extraction and turn them to regeneration

be long term in scope - 3 or 4 generations, probably 100 years or so

address the identity of the humans in the place to the place - undo the "otherness"

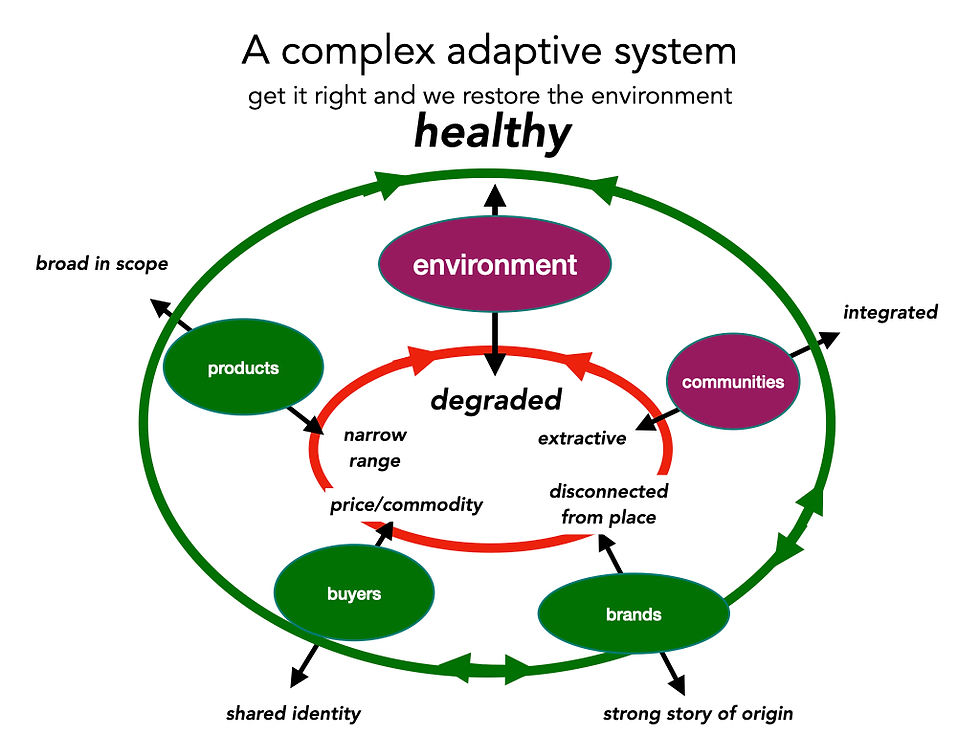

We think we can use the business to align the interests of the humans in the place with the health of the place, and that this system can be designed to create a perpetual virtuous cycle between environment and human.

It's complex and adaptive - and uses brands in a completely different way to change the consumer/market driven dynamic that has plagued us for so long.

So instead of brands that forge an identity between buyer and product but at the expense of planet, we design brands that first and foremost forge an identity between producer and planet which then extend to buyer. From the ecosystem out.

And then instead of seeing these brands as just ideas (or worse - marketing devices) we give them real form that can encompass the humans. We turn them into place companies that belong to the people in the place, where the strength of the brand and the prosperity of the people who own that company hang on the strength of the place the brand represents.

How might that work?

We make a brand company for the place Chigertei.

That company is co-developed and co-owned with the herders in Chigertei and the Good Growth Company.

It develops a place brand for Chigertei that tells the story of the people in that place, their love for the place and what they are doing to restore the place.

We make products that carry the brand and the story of Chigertei - scarves and blankets through Khunu, jumpers with Navygrey, maybe a couple of special "Chigertei" lines with friendly brands who want to do good.

A percentage of the final selling price (NB NOT the wholesale price or the raw material price) of the end product is returned to the Chigertei company in the form of a licence/royalty.

The result is more income for the herders but crucially income which is tied to and derived from the strength of their ongoing relationship with the place - the stronger the regeneration story the stronger the brand

We believe that these place brand companies can become the vehicle that reconnects buyers (let's please stop saying "consumer") back to nature through the story of origin owned by the humans in each place.

And that this shifts the pricing dynamics for herders to the other end of the chain - the stronger the regeneration story, the stronger the connection with the buyer.

Brand as identity - not as a marketing gimmick. Now that's an interesting thought.

Comments